8 min read

“Will A Poor First Quarter Ruin My Final-Year Grade?”

Introduction

In a world where it becomes more increasingly apparent and evident that our grades in high school (if you’re reading this earlier, and you’re younger, you have no need to worry one bit – I’ll explain later) end up determining how we do for the rest of our lives.

I know some of you will come and disagree, however, it’s sadly the truth. Our grades determine (alongside extracurricular activities, GPA, connections, personal achievements, you get it…) the path on which we end up years down the line. Good grades usually end up sending you down a good, or just an OK path, while bad or average grades result you with an OK, or below-average life afterwards.

Before I get far too ahead of myself, I’d like to say this: no, the world won’t end just because your first quarter was below exceptional. Chances are, you’re probably on this post because it was far below that standard. Below exceptional might be just an understatement.

I remember feeling that way in my sophomore year of high school. I didn’t do all that bad first quarter, but it was my worst quarter in high school ever. Sure, I still hadn’t even been in high school for half of it yet; but it felt terrible. My math grade was awful, along with my history, science, and I don’t even remember what.

Now when I look at it, it didn’t really change a thing.

When Do Your Grades Matter?

I was told that by the time I entered high school, only then would my grades matter.

They didn’t lie – except for the fact that if I treated it that way, I wouldn’t have been a year ahead in math. That’s besides the point.

What really matters, however, is that that’s when grades really mattered. When I was in elementary school, or in middle school, I always thought that what I did now; even if it was the smallest thing, mattered significantly. Let me tell you something: it didn’t.

By no means am I telling you to give up school for good, and only start re-giving your effort once you reach high school. No, please don’t do that. Rather, I’m saying that maybe you should just relax a little; especially while you’re still young.

Earlier, I mentioned that if you were young, that there was no need to worry about grades. That’s pretty obvious, and you likely already know that. The reason that’s true is exactly because of what I told you just now. How do they expect some random middle schooler that almost most definitely didn’t even know what they wanted to be in just 5 years (which, by then, you’d be a fully grown adult out of high school) to care enough about their own future and make such a life-changing decision? They don’t. No one really expects it.

Your grades matter in high school because that’s a new part of your life, a new -short- chapter. It marks the beginning of the chase for the life that you’ve always been dreaming of; starting with doing well in school, completing assignments, following directions, and doing as told.

How Negatively Does A Bad Grade Impact Overall GPA?

We’ll give two examples to illustrate this.

Person A just started the school year. Their grade is insignificant in this example. They start off strong with a majority of their classes, except two. For those two specific classes, they end up getting a C on a random summative (highly weighted) assignment, and a D on an early-given test meant for assessing knowledge on a few set of concepts. The difficulty and teaching style of each teacher is also insignificant.

Person B, on the other hand, has spent a few months in the school year already. Quarter 3 has just started, meaning that the first semester is already over, and completely locked in. There is no changing the grades they got before. And, guess what? There’s no need to. Person B did excellent the first semester, acing practically all classes. However, they get a new semester class and, with just two weeks passing by, receive an F (55%) on a summative written assessment. The purpose was to test their knowledge on a subject taught in class, and they had very little clue about what was taught.

Take a look at both situations. Both persons have seemingly similar grades for different classes. Yet, how bad would these individual grades affect their overall grade, for the year?

Let’s make one thing clear: what matters the most are your yearly grades. That’s the thing that colleges actually take a look at. Sure, maybe semester grades matter – but what really matters the most is how you do across all four years, NOT across 16 quarters or 8 complete semesters. We’re talking about professional establishments here, not just ordinary places there selecting you based on a specific criteria.

Example Analyzed

So, in either situation, who is more screwed?

I want you to answer this question for yourself before the analysis I’ll provide below. I want it to be completely in-depth so that you understand (just as well as I do) why X and Y matter relatively to Z; the final-year grade.

Your final-year grade is made up of dozens of formative and summative assessments. Assessments are not tests, just tasks. I’d also like to make it clear that your school may not grade the same way as my school does (and that’s perfectly fine), so please understand this. By formative assessment, I mean an assignment-like task. These don’t affect your GPA as much, but still matter nonetheless. These are like your homework assignments, in-class assignments, quick side-projects, or literally anything that is quick and fast-paced.

Summative Assessments

Summative assessments are the big ones. These folks are actually grades heavily, and will tank your GPA if you score poorly on it. These are your projects (self or group), tests, occasional quizzes (can also be formative), presentations, and rare assignments. Any assignment that actually does meet this criteria is usually packed with contents and requirements, so therefore it can be possible. Summatives are great when your grade in a class is low, for a more stabilized grade (more summatives stacked up means that future ones won’t affect you nearly as much), and if you’re confident in X class.

However, summative assessments can also be really messed up at times. In my school, if you scored poorly on a summative assessment, your grade would absolutely collapse into the abyss. But, if you scored well, even if your grade sucked, it wouldn’t have as big of an impact; more like, 35-40% Yeah, I know, kind of unfortunate really.

Weighting

Formative assessments are the ones that will easily stack throughout the year, but -relatively speaking- won’t do much. For example, if you have a D in a class, and get an A on the formative assessment, your grade might not go up at all. Sure, it might go up 1 or 2%, but usually no more than that, even if your grade is absolutely in the gutter and if you scored 100%. It doesn’t matter.

However, if your teacher gives you lots of these formative assessments, and I mean a lot – we’re talking several per class; then, it might be a considerable method to get your grade up (but only in the short term).

What do I mean by this? (sorry if I’m dragging this out)

Formative Assessments vs. Your Grade

We’ve already discussed what formative assessments are. They’re the simple, casual, and day-to-day assignments that your teacher regularly assigns you. These tasks, if your grade is really bad, will help a ton if done well, and consistently.

However, my problem with formatives is that at one point, they practically don’t help at all. For example, if your teacher grades formatives out of 10 or 20 points on the regular, and you have a low A or high B in the class (and still want to improve it), it won’t do much. I’ve seen this a handful of times in my own personal experience, and it almost always happens. Unless a formative is worth 100 points or more (yes, it’s possible) will it actually do anything at this point.

Therefore, if your teacher regularly grades formative tasks on a scale of 5 or 10 points, and you want to get A- or higher, it really isn’t very likely; especially not if your teacher doesn’t post assignments very often.

Technically, you could also apply the same idea to summative assessments too. If its point scoring is too low (we’re talking 5 points or less), even if you have a B in the class, it won’t do anything.

The key to a better grade in the class is actually very straightforward: a better grade on a highly-weighted assessment that can either make or break your grade, overall, for X class. It’s kind of like making a risky bet, but also not; since in this situation, you can actually prepare for whatever test or quiz is to come. And projects on the other hand? Although they suck the most, especially presentations, they’re also the easiest to squeeze a very abundant amount of points from. However, your teacher probably won’t assign these too regularly.

Rooting These Ideas Back

So, not going back to the example yet, we need to think about this once again.

Actually, wait no, YOU DO.

Just think for a moment. What class did you do poorly on? Does that teacher regularly post work for you to take advantage of? Or, do they rarely ever post anything? (or simply grade everything last-minute)

Recommendation: You know your teacher best. Some teachers post so much work, while others don’t. Tailor your approach to what you know will work.

Example Analyzed (revisited)

Reverting back to what we were saying before about the two persons, and the question of: who is more screwed?

Neither one is.

If you seriously had to think that through, then you might need to re-evaluate the way in which you perceive education, or at least traditional schooling. Neither person is in that bad of a situation, and it’s because of the time they have left to make up their mistake. Just for simplicity, and realism, we’ll say that neither student is eligible for extra credit opportunities for that assignment, or at all.

In that case, one thing’s for sure: both students need to make sure that whatever assignment comes, that they do well on it. But of course, you knew that.

What you probably didn’t know however, is the math behind it.

Example #2 (Using Math & Real-World Weighting)

For this example, we’ll imagine an imaginary student. Let’s call him “no-name”, because I can’t be bothered to think of names. No-name is currently a senior in high school, and is a particularly good student. He already has his eyes set on what college he wants to go to, and what he wants to do in life. He finishes first quarter however, and ends up with a D- (60%). Some of you might believe that it no longer really matters, given that colleges don’t really pay attention to Senior year; however, you can’t really say that in this situation. It’s only Q1.

You can probably say one thing for sure: he’s going to have to put an incredible amount of effort just to pull himself back up. And, you’d be completely right.

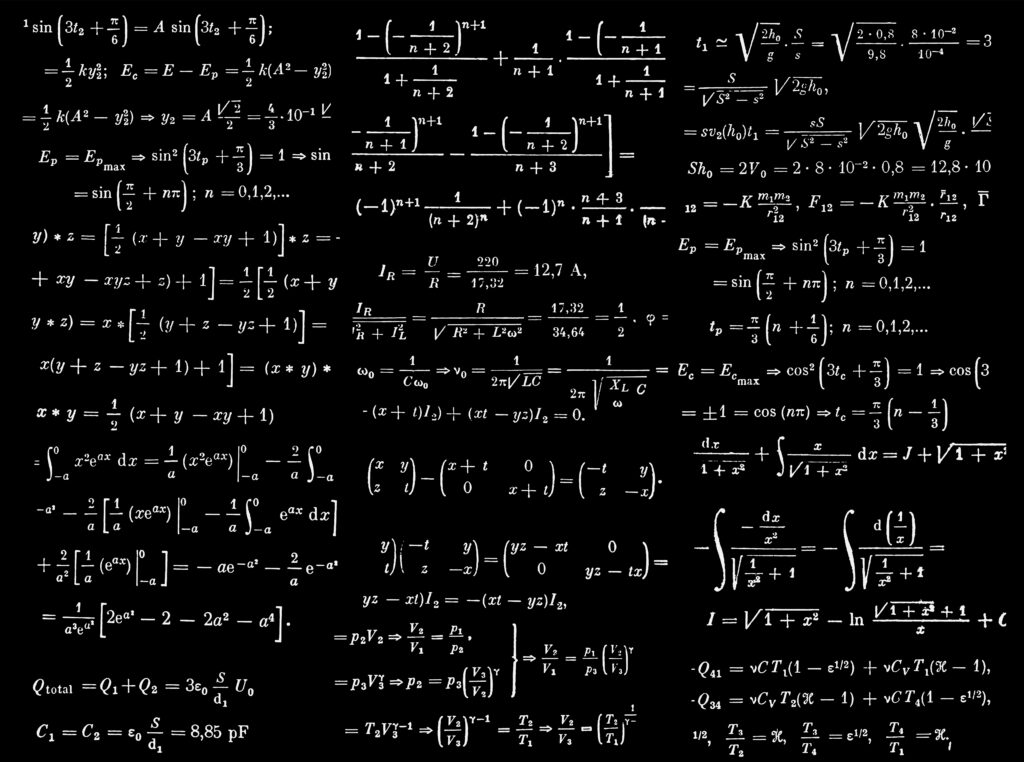

Complete Calculations

For our case, we’re aiming for an aggressive target: 95%+

That’s our full-year target number.

First, let’s calculate the first quarter’s contribution to his overall, final-grade.

First Quarter Contribution = 60% x 25% = 15%

This means that his first quarter has already contributed to 15% of the final grade, according to an equal 25% weighting per quarter, for every year. No, this is not good. This means that in order to secure an 100% overall, he’ll need to earn 85% overall back. This is impossible given the current quarter 0.25x weighting.

To achieve a final grade of 95%, No-name will need 95% – 15% = 80% from the remaining 75% of the total grade (the second, third, and fourth quarters combined). This means that No-name needs to average over 100% in these three quarters, consecutively, to make up the difference. This is an unfeasible task; but nonetheless, we’ll still continue with the calculation.

Since it’s not possible to score above 100%, unless heavy (we’re talking summative-heavy) extra-credit opportunities are given, No-name will need to aim for a higher average across the three remaining quarters to make up for the low first quarter.

The contribution to the final grade from each quarter is 25%, and the remaining 75% must average to 80% to make the final grade of 95%. This means No-name needs:

Required Average per Quarter = (80%/75%) x 100 => 106.67%

This means that No-name would need to average 106.67% PER QUARTER (AVERAGED). This is quite literally impossible, because it’s above 100%, and for many of you, getting 6%+ worth of extra credit is no option at all.

Formative & Summative Percentages (Re-Calculation)

Introducing the formative and summative grading introduced previously, we’ll see if No-name could score enough (realistically) to still balance out his average. For this calculation, we’ll assume that formative assessments are worth 30% and that summative assessments are worth 70%. We’ll also assume that No-name scores 100% across ALL summative assessments.

100% x 70% = 70%

If No-Name scores 100% on summative assessments, the contribution to the final grade will be 70%.

Since summatives already contribute 70% per quarter, No-name needs to make up the remaining 30% to reach the 100% total per quarter.

100% – 70% = 30%

To meet this requirement, No-name would need to score 100% in formative assessments as well, for the remaining three quarters. (both average to exactly 100%)

Such a grade would require flawless (no less, no more) performance.

The Answer To Your Question (in as few words as possible)

Grades, on their surface, are just percentages. They are numbers, and are manipulated by other numbers. If you get a number, and multiply it by what you have, no matter how poorly your school weighs grades, and if it weighs bad grades more than good grades, your grade has to go up. There’s no mathematical rule that’s stopping it.

Therefore, the straightforward logic is to 1) do more work and 2) do better on it. Simple. But not easy, and if anything, it will actually destroy your mental health too.

I seriously suggest that you, however bad you did in the first quarter, you put it into a calculator, and calculate the final result, finding an approximate average. The reality is that if you scored so low in the first quarter (specifically), you probably have no way of making a U-turn with your academics in that class and somehow pulling off a miracle like the one above. It’s relatively impossible.

However, if your concern is in regards to another later quarter (that isn’t Q1), then you’re talking about a completely different scenario. In that case, you might just need a quick reboot, and you’re good to get back to work.

If you do the math, find the probabilities of every possibility, and are ultimately realistic enough (how much you care doesn’t matter; that’s not a value), then yes, you could theoretically get your grade back up. HOWEVER, depending on how poorly you scored in the first, or whatever quarter, a possibility for a “comeback” can potentially be impossible. Don’t expect to magically get a 98% for the full year if in one quarter you slacked off and got a 57%. You’re asking for a wish that is legitimately impossible to make a reality. Just don’t screw up, not that bad.

How To Perform These Same Calculations Yourself

- Step #1: Define key values and variables – Before calculating, it’s important to define the key values in the problem:

- Final Target Grade (T)

- First Quarter Grade (Q1)

- Weight of First Quarter (W1): The percentage of the total grade that comes from the first quarter (for me it was 25%; for you, it could be different)

- Weight of Remaining Quarters (W2)

- Grade in Summative Assessments (S): The average grade the person expects on summative assessments for the remaining quarters

- Grade in Formative Assessments (F)

- Step #2: Calculate the contribution of the first quarter grade – The first quarter grade contributes to the final grade based on its weight. The formula is:

- First Quarter Contribution = Q1 x W1

- Step #3: Calculate the remaining grade needed – The remaining grade needed is the difference between the target grade and the contribution from the first quarter

- Remaining Grade Needed = T – First Quarter Contribution

- Step #4: Calculate the average required for the remaining quarters – Next, you need to calculate the average grade required across the remaining quarters

- Average Required for Remaining Quarters = Remaining Grade Needed / W2

- This will give you the overall average needed from the remaining quarters to reach the target final grade

- I’ll abbreviate this to “ARRQ”

- Average Required for Remaining Quarters = Remaining Grade Needed / W2

- Step #5: Break down the ‘Required Grade’ into SUMMATIVE and FORMATIVE assessments – The total required grade from the remaining quarters needs to be divided into formative assessments and summative assessments

- Required Formative Grade = ((ARRQ x Weight of Formatives) / (Weight of Formatives + Weight of Summatives)) x 100

- Required Summative Grade = ((ARRC x Weight of Summatives) / (Weight of Formatives + Weight of Summatives)) x 100

- These values also depend on your school, or in some cases, your teacher. Some of my teachers graded by 30%-F:70%-S, while others did 40%-F:60%-S. It all depends.

(what if I get extra credit?)

In that case, if you plan to rely on extra credit too, or if you can adjust performance in one category, you can also re-distribute the required grades based on the expected performance in each type of assessment.

- For example: If they expect a perfect score in summative assessments, they can lower the requirement for formative assessments, or vice versa.

Using These Formulas For The Example Earlier

We’ll be implementing No-name’s same values for this use-case:

Given:

- Target Grade (T): 95%

- First Quarter Grade (Q1): 60%

- Weight of First Quarter (W1): 25%

- Please note: this all depends on your school or teacher.

- Weight of Remaining Quarters (W2): 75%

- Weight of Formative Assessments: 30%

- First Quarter Contribution = 60% x 0.25 = 15%

- Remaining Grade Needed = 95% – 15% = 80%

- ARRC = 80%/0.75 = 106.67%

- This is not possible because it exceeds 100%. This means achieving 95% overall is not possible after scoring a 60% in the first quarter. However, if the first quarter score were higher, this would be feasible.

- Required Formative Grade = ((106.67% x 0.30) / (0.30 + 0.70)) x 100 = 32%

- Required Summative Grade = ((106.67% x 0.70) / (0.30 + 0.70)) x 100 = 74.67%

In this scenario, even if No-name performs perfectly in summative assessments (100%), they would need to also get 100% on formatives as well, and this still would not be enough for a final grade of 95% due to the very low score in the first quarter.

We are confidently able to make this assumption given that formatives award exactly 30%, and somehow, No-name needs to pull off 32%, and approximately 5% extra from summatives. That is outright impossible, and requires immense extra credit to combat.

If you were being realistic, and still talking about an extremely smart student, the calculations would look more like:

- ((95% x 0.30) / (0.30 + 0.70)) x 100 = 28.5%

- ((95% x 0.70) / (0.30 + 0.70)) x 100 = 66.5%

Doing that would give you very different values.

Conclusion

You can still score above the limit that you have set for yourself. Be generous, but be realistic. At the end of the day, your mission is to score as high as possible in as little time as possible; no matter the effort. You coming here, and being willing to know the math behind the probabilities means one thing only: you sure care a whole awful lot.

I wish you luck. You can do it, unless the math is not on your side. In which case, there is absolutely nothing that can be done.

(hey… if you wanna read a similar post about recovering a poor semester, I suggest you read this. You might like it)