x min read

“Test” Images – Unsplash.com

Introduction

AP season is here. It’s actually been here for the past month or so. I know that I’m just getting it to it now. It’s late, and by now, you’ve probably already entered all five phases of grief.

But hey, don’t worry. We’re in this together, literally. History has me by the throat, and my main goal is to pass, ace, that test to prove that you don’t need months of preparation just to ace 1 test. Now, to live up to this expectation, I need to achieve and set realistic expectations.

Yet, expectations don’t really seem realistic. I have less than 2 weeks -as of the time that I’m speaking- to study for my exams. Do you really think that you can stop what’s coming? My answer: potentially.

Enough speaking. Let’s learn how to write a bomb SAQ. Together.

Define

SAQs are defined as short answer questions, whose purpose is to test your knowledge, alongside your analytical skills. That’s it. Not much.

Short answer questions are very simple and straightforward, but aren’t easy. In my experience, to really do well on an SAQ, you need the following three abilities:

Skills

- Interpretation

- Extraction

- Writing (quality, speed, effectiveness)

To do well on any test, you need to memorize information. To do well on an SAQ, you need to know how to effectively interpret and extract information.

Examples of interpretation:

- How do I know what the prompt is asking/asking for?

- How do I recognize the POV of the writer and the purpose for which they are writing, when not explicitly stated?

- What big idea is/are the author(s) talking about?

Examples of extraction:

- Where do I find X?

- How do I integrate evidence piece Y into my answer?

- How do I assemble an answer in the jungle of words that there are in the prompt?

Before I explain how you can hone those two skills, I firstly want to talk about writing quality, speed, and effectiveness. These three, alongside the other two skills, will help you dominate ANY SAQ that stands in your way. Realistically, even if you knew little to nothing about the material that you’re studying, you still can answer that question with a high-quality answer if you’re willing to.

How To Write Perfectly (Literally)

There are three points that we need to cover when it comes to perfect, good writing. Let’s start from the top.

Writing Quality

First, you’re gonna need a good vocabulary structure. Specifically when I say this, I mean that you’re going to have to be familiar with vocab words in your topic range that you a) must be familiar with and b) are affiliated with the topic you’re researching.

So, no you don’t need to go out there and just look through a dictionary for an hour a day just to learn new words. Sure, it might help for other reasons; but not with the AP exam. For example, if you were taking AP World History: Modern, some terms that you should be confident with include devshirme, capitalism, or the mit’a system. Again, they aren’t words used traditionally in our everyday language. But in history talk, they are used commonly. Build familiar and get used to those suckers.

Second, you need to learn how to structure your sentences and paragraphs in a way that makes your argument clear and logical. Remember, when it comes to writing arguments, it really is just an opinion. In an academic sense, opinions aren’t wrong (for those that are confused why opinions aren’t ever wrong in any sense, just think of a really stupid opinion on something; see what I mean? An opinion that’s just straight up incorrect). So, you shouldn’t be afraid of anything. Walk your talk, and say what you gotta say. What matters is how you say your message, not what you say. Once you learn that, things get a lot easier.

Pro Tip: Read Between The Lines

If your question isn’t based on an argumentative style answer, then your approach to step 2 is gonna be slightly different.

Before all of that, you firstly have to understand that your answer is almost entirely dependent on what you got going on in the back of your brain. In other words, what do you know? Good thing here is that studying pays off. Bad thing is that you are going to need to study in the first place.

However, that doesn’t mean that you’re entirely screwed. A few things that you can do aside from studying like every other student is:

Didn’t Study? No Problem.

- What is the question asking for, exactly? Is it a description, an explanation, a process, or a series of facts?

- What key terms is the prompt using? This should give you a good idea as for what the question demands?

- Start with a direct statement that addresses the requirement of the question. This could be a definition, a specific fact, a date, or a concise explanation.

- Don’t overdo it. Use clear and specific language that communicates your answer effectively without excessive detail.

- If it’s an image, you have it easy. The only obstacle in your way is image interpretation.

- If you aren’t provided with an image, and you have no background knowledge to depend on, then you need to make connections. In other words, what this means is that you need to connect what you know to what you need to know.

- For example, if you’re taking an AP history exam, you’re guaranteed to know -at least- that Christopher Columbus discovered the Americas. From there, you might then create another connection (e.g. he did it during 1492, he was from Spain, he didn’t mean to actually discover the Americas), followed by another (e.g. the Americas was so new and filled with luxuries and beauties not seen before, he held intentions to capitalize on opportunity – as he originally planned to do anyways), and another; all the way until you finally reach a conclusion.

- Sure, it’s lengthy and probably sucks. But, what would you rather prefer? Just accepting failure and admitting that you should’ve studied or trying to pull a smart attempt to get yourself back together?

- For example, if you’re taking an AP history exam, you’re guaranteed to know -at least- that Christopher Columbus discovered the Americas. From there, you might then create another connection (e.g. he did it during 1492, he was from Spain, he didn’t mean to actually discover the Americas), followed by another (e.g. the Americas was so new and filled with luxuries and beauties not seen before, he held intentions to capitalize on opportunity – as he originally planned to do anyways), and another; all the way until you finally reach a conclusion.

“How to Answer an SAQ: Structure, Scoring, Writing Tips & More”

How To Write Perfectly (cont.)

Third, avoid writing too much. At the end of the day, sure, it might look nice when you swish up a big paragraph with a word count of 200. But, be honest, you’re just overdoing it at that extent. Your goal is to get in, and get out. You write what you need to write, and just end it there. Save yourself some time, and especially, your sanity.

Writing Speed

Practice actually works here. The idea is that you want to train your brain to work under pressure. By doing this, your brain will slowly but surely adapt to terribly work conditions and then get used to them. Although it might suck in the beginning, it’s a great way to train your mind and soul to work together like peanut butter and jelly and make for the perfect combination for success.

So, here are my two steps:

- Firstly, learn how to write faster. Whether that’d be by hand or by computer. Learn to endure harsh conditions when writing with your hand for hours on end or keyboard (if you’re up for that).

- Secondly, and not mentioned yet, you need to learn how to outline what you’re going to write out as fast as possible. In other words, start drafting templates or formulas for your writing. If you’re writing an argument, craft a specific formula that you can follow every single time, and get the same good consistent score.

Writing Efficiency

Before you even continue ahead, you need to read this. READ THE QUESTION!!! Seriously, I cannot tell you how many times I’ve read a question, answered it, and then receive my test back a few weeks/days later and see me lose a point on that exact question all because I misread it. Under pressure, your brain acts differently and is more prone to stress.

That stress consumes and takes advantage of you, even when you don’t notice it. If there’s anything that you MUST ALWAYS be sure of, it’s that you know what the question is asking. Read it, make sure you get what it’s asking through your thick skull, and then proceed.

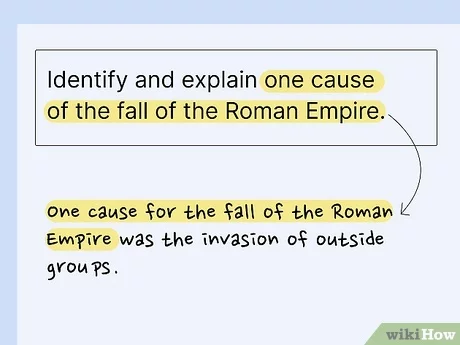

With that out of the way, my next time would be to use the ACE (answer, cite, explain) method:

- Answer: Directly answer the question in your first sentence.

- Cite: Provide a specific example or piece of evidence.

- Explain: Connect your evidence back to the question, explaining how it supports your answer.

Interpretation

Aside all the other skills in this post, interpretation is probably the most important one. Mastering it alone won’t get you the score you’re looking for, but it’ll get your foot in the door.

To make it easy, when you interpret a question, you’re trying to understand what it’s asking. You’re trying to decipher the deeper meaning behind the prompt. Let’s break this down:

- Decoding the Question: The first step is to thoroughly read the SAQ to grasp what is explicitly stated. This includes recognizing key verbs such as “describe,” “explain,” “compare,” or “summarize,” each of which delineates a different approach to answering. For example, “describe” might require a detailed depiction, while “explain” might need an exploration of causes and effects.

- Contextual Understanding: Interpretation also involves contextualizing the question within the broader themes of the subject matter. This might mean relating the question to specific theories, historical periods, or scientific principles that have been covered in your coursework. Understanding the context can significantly shape the direction and depth of your response.

- Inferring Implicit Requirements: Beyond what is explicitly asked, effective interpretation requires sensing the underlying questions or the implicit demands of the SAQ. For example, a question might ask for an explanation of a concept but implicitly expects examples to illustrate your point.

Extraction

Now that you know what the question is asking, and what the source (if there is any) is asking, you need to understand how to extract the information from X and use it in your answer.

Of course, there lies an obvious problem. Extract what? What if it’s just a prompt, just a question, and nothing else? What am I supposed to extract information from for my answer, if there’s nothing to?

As an important side note, this step (extraction) only goes for certain SAQs. For example, history short answer questions might (and probably will) provide a source to answer to. You’ll be provided with a document, letter, image, drawing, graph, or something to write on. From there, your job is to just write.

- Underline, Highlight, & Find Key Focuses: Find topics or subjects in between the lines (unless they’re just blatantly in the text) that answer the question, or that help your formulate an answer.

- Identify the main idea: Determine the central concept or argument that the text revolves around.

- Note key details: Pay attention to supporting details that explain or illustrate the main idea.

- Summarizing sections: After reading a section, summarize it in your own words. This reinforces what’s important and clarifies your understanding.

- Generate questions: Before diving deep into the text, list down the questions that you need answers to. This sets a purpose for your reading.

- Skim for keywords: Look for keywords related to your questions as you skim the text. This helps in quickly locating relevant information.

- Identify headings and subheadings: These often outline the main topics and can guide you to the sections where answers might be found.

- Look for lists and bullet points: Authors often use these to summarize or emphasize information, making them valuable for quick extraction.

- Integrate information: Combine information from different parts of the text to form a comprehensive answer.

- Apply to the question: Make sure that the information directly addresses the specifics of the question. Adjust the level of detail based on the requirement of the question.

- Cross-check with the text: Ensure that your answers are supported by the text and that you haven’t misinterpreted any information.

- Refine for clarity: Simplify complex answers and clarify any parts that might be confusing or vague.

“Highlight” Images – Unsplash.com

Conclusion

If you want to do well on your next SAQ, just know that it’ll all be ok if you’re willing to invest even a little bit of time. Sure, studying sucks, and there are hundreds of other things that you could be doing, but hey! We’re here to help. So maybe it’s not all bad, right?

Just like the SAQ, there are various other obstacles you must overcome to do well on that final exam. Why not try mastering the FRQ this time?